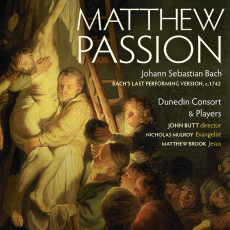

JS Bach Matthew Passion - Dunedin Consort - Gramophone

Having swept the board with their Award-winning Messiah, John Butt and the Dunedin Consort and Players proceed headlong into the summa of dramatic religious masterpieces. One imagines, however, that this highly singular approach has been marinating in Butt's mind for years. This is a reading (the first to draw on the 1742 performing version with its re-allocation of continuo instruments) where scholarly and musical penetration is indivisible in the strength of the approach and the unswerving commitment of the "players".

And "players" they are - except that Butt argues here for a new dramatic understanding of the Matthew (note the curious de-sanctification) where the work challenges the notion of "parts" in an opera, towards various "voices" which reflect the listener's absorption of the conflicting positions - both biographical and emotional - of the main protagonists and the most far-flung thresholds of human experience. This is achieved using the main singers, from the eight principal voices, in different contexts. Hence, as Butt explains in his illuminating note, the Evangelist may rally us to lament as an allegorical "Daughter of Zion" in the opening chorus before darting in and out of the story in recitatives, chorus, aria and chorales, mixing up the past and present, first person and third person, in a web of intense and coherent narrative and reflection.

All of this presupposes a one-to-a-part troupe where all these subtle character combinations can be perceived. With such a spectacularly clear and balanced sound from Philip Hobbs, these ambitious perspectives are powerfully realised; refreshingly, too, Bach's "novel in sound" is presented in a small inter-reliant ensemble without the need for tiresome dogmatic mantras on historical rectitude. Indeed, often so entwined are the textures that singers' vowels are shadowed by instruments in a close-knit rapport of exceptional immediacy.

For those steeped in both recent and old schools, this performance will resonate with both, though it is not always so easy to summarise how. The thread of intensity is achieved largely by the focus and roundness of the Dunedin Consort's palette, the thrusting legatos (when called for) and the welcome presence of a strong, directed bass-line. Like Karl Richter's 1958 recording - also recorded in only four days - momentum and expressive concentration are the sine qua non. In smaller units, one witnesses the flexible interactions between sections, the "appogiatur-ated" phrasing, luminous textures and fast, forthright

chorales - all in the modern gait.

Such responses are relatively superficial because Butt's St Matthew is truly original in spheres resonating beyond established parameters. In his story-teller, he has found an Evangelist with the candid vulnerability of Helmut Krebs. Yet Nicholas Mulroy brings his own striking naturalness of delivery, clarity of diction and honesty. At the start of Part 2, especially, there are moments of disarming reportage, such as the encounter with the High Priest where the Evangelist conveys a sickened response to Christ's humiliation and a gutting catch in his voice at the emptiness of Peter's denial.

Yet it is Mulroy's identification with the outstanding Christus of Matthew Brook which raises the stakes in this performance. The timing between the two and the realism of the musical choreography is both remarkably patient and animated. When Jesus goes to Gethsemane, the austerity of the brief exchanges, between narration and action, implies more than just the Gospel event of Christ's retiring prayer. The coloration explores, in microcosm, the Evangelist's own heartfelt identification with the drama into which he seems unwittingly drawn, and which heightens, almost unbearably, as the work unfolds.

The only downside of a single-part St Matthew is that, while the singers - in Butt's words - "become familiar to us as the piece progresses" ("hearing them take several roles enhances their actual reality to us"), this only works to advantage if they have the tonal and musical range to sustain such an extended and exposed vision. For all the stylistic nuancing and deft ensemble work of the sopranos, their arias rarely lift themselves beyond the generic. "Ich will dir" sounds unsure and snatched and "So ist mein Jesus gefangen" fails to demarcate the almost cosmic mystery ("moon and light have set in their anguish") alongside the admirable discipline of the crowd's graphic interjections. This is a moment where Fritz Lehmann's shimmering 1949 reading has rarely been surpassed.

Among the disappointing arias, neither "Aus Liebe" nor "Können Tränen" (a struggle for Alto 2) approach the exceptional interest and quality of the finest examples. The questing Clare Wilkinson carries on her form from Messiah with a heartfelt "Erbarme dich" (Simon Jones's obbligato violin playing is wonderfully poetic, as is Jonathan Manson's mesmerising viola da gamba in "Komm, süsses Kreuz"). Brook's "Mache dich", prefaced by arguably the most assuaging recitative in musical history, is little short of masterful with the range of colour, risk and gentle courtesy he brings to this superlative emblem of unswerving faith.

No recorded St Matthew Passion, as I discovered in an exhaustive "Collection" in 2005, comes without its blemishes but few parade such a compellingly fresh and raw realism, one so strongly identifiable by its wilful clarity of intent that it asks new questions about what this great work can say to us.