Astrig Siranossian - Dear Mademoiselle - The Classic Review

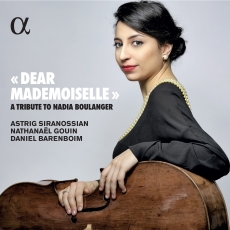

Astrig Siranossian’s newest release is in some ways a reflection of her wider discography, which shows an artist who has explored a wide range of music from Schubert to Gubaidulina. As a tribute to Nadia Boulanger, “Dear Mademoiselle” is a thoughtful curation of works by Boulanger, Stravinsky, Glass, and others.

Boulanger wrote her Three Pieces originally for organ, but later transcribed them for cello and piano. The E-flat minor (track 7) is breathtaking. Siranossian, especially in her upper register playing, has a supple yet highly expressive tone quality; her pianissimos also bring to the work a magical presence. Barenboim (himself a student of Boulanger) uses his own straight-stringed Maene concert grand. It has a noticeably pristine sound – the sympathetic resonance we’d perceive on a normal piano is not as present here – yet, this does not rob the instrument of its richness.

But it’s not just about the piano itself: Barenboim contours his melodic lines beautifully in the momentary interchanges with the cello. These moments of convergence between the instruments are what gives depth to Boulanger’s delicate textures. At the heart of the A minor (track 8) is a canon. In keeping with the character of the original version for organ, Sirossian and Barenboim present the hymn-like melody with nicely blended harmonies. But where the organ more or less has a homogeneity of timbre, the cello and piano bring a more conversational quality to the work: each has expressive nuances that make its distinct personalities come through.

A shift of character between the sections also transforms the work as a whole into a montage. The performers imbue the middle section with an intensity that highlights Boulanger’s vibrant and exploratory harmonies. The outer, almost modal-sounding sections, on the other hand, are the calm and meditative complement. I found the recapitulation especially captivating as an introspective echo of the opening.

Philip Glass’ Tissue No. 7 (track 14) is another excellent performance. As part of a larger set written for the movie Naqoyqatsi (2002), the work is a broad canvas of constantly yet subtly evolving tonal colors. The diaphanous tones of the 1960 Steinway used here really come through, thanks to a sensitive performance by pianist Nathanaël Gouin. Even in repetitions of the same harmonies, he produces different gradients that build a dimensionality within the minimalism. Sirossian’s well- controlled bowing helps the cello line emerge as both a melodic figure and a foundation upon which the piano part moves.

Elliott Carter’s Cello Sonata is a reflection of two major but opposing influences: Boulanger the traditionalist and Charles Ives the modernist. Carter seemed to embrace the theme of dichotomy in his description of the work: “I immediately began to consider the relation of the cello and piano…[and] that since there were such great differences in expression and sound between them, there was no point in concealing these as had usually been done in works of the sort.” The first movement especially speaks to this idea. The cello’s resounding melody is the antithesis of the dry, pointillistic piano line. We might anticipate that the stylistic clash is hard to get past, but the performers make it work by approaching their diametrically opposed parts with conviction and consistency. The cello is rich and expressive, while the piano is appropriately impersonal and clock-like. It’s interesting to note that the final moments of the Allegro (track 13), revisit the first movement but with the instruments switching parts. The sound is distinctly different; at the same time, though, we hear vestiges of resonance in

Siranossian’s pizzicatos and an emotional coolness in Gouin’s closing lines that brings the work full circle.

Soul bossa Nova by Quincy Jones (track 16) adds an element of fun to the album while showcasing the performers’ stylistic versatility. Although not as bold as Jones’ 1962 big band version, it has a suave elegance that beckons the listener to join in. The transcription has a nod to some signature jazz elements as well, such as Gouin’s improvisatory passages or the pizzicatos that mimic a rhythm section’s double bass.

The concise liner notes give us just the right amount of insight into Boulanger’s life and relationships with the featured composers. Paired with the sincere performances, this album helps us appreciate Boulanger’s lasting legacy. An enthusiastically recommended listen.