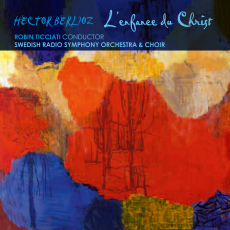

Robin Ticciati - Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra - Berlioz: L'enfance du Christ - International Record Review

L'enfance du Christ was greatly admired by both Brahms and Debussy, some indication of the width and of its appeal. It was also the work that transfixed the young Colin Davis, the a clarinettist ignorant of Berlioz, and in his conducting career he often returned to it with performances that are among the finest recorded. Robin Ticciati's new version makes less of the drama informing the whole story of the Flight into Egypt than Davis did, but it is sensitive and scrupulous, responsive to the subtleties of Berlioz's score and the emotions of the participants. Alistair Miles appears to be the singer of Herod as well as the hospitable père de famille in Part 3, something countenanced by Berlioz. He gives fine performances, haunted in Part 1 in Herod's anguished ‘uneasy lies the head that wears the crown' aria, as even this infanticidal monster is shown capable of suffering himself, and then warm and benign in Part 3 when the welcome denied in Part 1 is extended to the fleeing Holy Family. Stephen Loges is a tender, anxious Joseph to the gentle but also distinctive Mary of Véronique Gens. A fine Berlioz singer, she has an acute sense of his often unusual phrasing expressing a latent simplicity, and ‘O mon cher fils' is beautifully done. Yann Beuron judges the role of the evangelist Narrator sympathetically, eloquent but not intervening too personally in the story.

The work needs unusually careful judgement in the interpretation. As the distinguished theologian Ben Quash points out in a brilliant essay in the booklet, there is an analogy with painting: ‘The centre of a triptych makes sense of the outer panels; the outer panels amplify the meaning and relevance of the central scene.' Ticciati handles the centre of the work excellently, with the sole reservation that the beautiful Shepherds' Farewell, the little piece around of which this pearl of a work is formed, is given a slightly waltz-like lilt that does not help its serenity. In Part 1 the soothsayers stumble along with a suitable touch of comedy in their gauche 7/4 rhythm; the rather superfluous trio in Part 3 for flute and harp is prettily played; and there is real attention, on the part of both conductor and engineers, to the often tricky but effective demands made by Berlioz throughout. At the end of Part 1, the orchestration includes instruments playing at different dynamic levels, with the organ (whatever kind of instrument is used) celestial and ‘tremblant et doux', and as the offstage choral singers dissolve into soft ‘Hosannas', they are asked to make their effect with complex instructions from Berlioz in his score about how to mute their voices in a sourdine vocale (including by turning their backs on the audience). There is no knowing whether or not these injunctions have been strictly obeyed, but the effect is loyal to what he seems to have wanted. By Part 3, the orchestration has grown remarkably lighter, something on which Ticciati has a sure grasp. Hugh McDonald's fine essay in the booklet has seen previous service, but now adds some fascinating new observations about Berlioz's awareness of earlier French works. It is interesting to learn that composers now as little known as Félicien David and Ernst Reyer were direct influences.