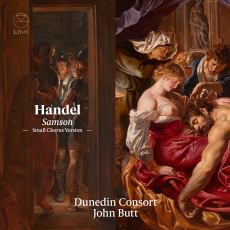

Dunedin Consort - Handel: Samson - Early Music America

Of the Handel works that get the most press these days, Samson is not exactly at the top of anyone’s list. The nearly three and a half hours of its original 1743 version is hardly fare for a casual evening out, and as part opera, part oratorio, it doesn’t fit neatly into modern expectations for either genre. But in its day, it was one of Handel’s most popular pieces.

Handel had been living in London since 1712, and works of his based on English texts gradually became much more popular than his well-known Italian operas. He completed Messiah in 1741 and immediately began composing Samson, based on a text by John Milton (of Paradise Lost fame). Derived from the biblical story of Samson and Dalila, the libretto starts in medias res; Act 1 depicts an already-imprisoned Samson receiving visitors on a festival day, Act 2 highlights Dalila’s apology and Samson’s argument with Harapha, while Act 3 ends with Samson’s death. The work was a smash and had more performances in its first season than any of Handel’s other oratorios.

Many of these performances, however, were the results of later edits by the composer, who made significant cuts and added new bits, like the famous Funeral March. Modern recordings and performances have tended toward those shorter, newer versions. But here, John Butt and the Dunedin Consort reimagine the full original version — not once, but twice. While we don’t have tons of information about Handel’s choruses, as the beautifully written liner notes explain, it seems that for some of these bigger works, his soloists sang alongside a choir of men and boys; however, in other instances, the chorus comprised only the soloists. Neither of these choral options has apparently been recorded before now, and on this massive three-CD set, the consort provides both options. (The CDs contain the version with the Tiffin Boys’ Choir, while the soloist-only version can be bought separately or downloaded with purchase of the CDs.)

Any one of these new historical approaches — the original 1743 version, or either of the two choral options — would be sufficient on its own to render this new recording a necessary addition. But in case those were not enough, rest assured that the recording itself is superb. Each of the eight soloists is incredibly strong and perfectly suited to their respective roles. Joshua Ellicott is a compellingly sympathetic Samson (listen in particular to “Total eclipse”), especially in contrast to Sophie Bevan’s Dalila, whose dark-toned allure is practically palpable. Bevan’s sister, Mary Bevan, is also in the cast, taking on several soprano roles (Virgin, Israelite Woman, Philistine Woman) to which she lends a similarly sensual approach; her concluding “Let the Bright Seraphim” is a standout.

The last of the soprano roles (Virgin, Philistine Woman) are performed by Fflur Wyn, whose comparatively lighter voice adds a lovely sense of nimbleness. I was particularly struck by the warmth and richness of Jess Dandy’s contralto, perhaps nowhere so much as in “Return, O God of hosts.” Ellicott aside, the rest of the male cast is up to the challenge laid down by the women. Hugo Hymas (Israelite, Philistine, Messenger) has a marvelously supple voice, lending an apt sense of drama, while Samson’s father, Manoa, is sung by Matthew Brook, who is in equal parts contemplative and authoritative. Lastly, the lone bass, Vitali Rozynko, convinces as the sarcastic, cruel Harapha, especially in the recitative “With thee, a man condemn’d.” Soloists aside, the chorus is bright and brilliant from start to finish, and the youthful trebles add a welcome shimmer to the topmost lines, nowhere as clearly as in “With thunder arm’d, great God, arise!”

The Scottish orchestra is every inch the equal partner; listen, for example, to the vibrant, precise ensemble playing at the beginning of “Honour and arms” or the wonderful interplay between the bright brass and the chorus in the concluding “Let their celestial concerts all unite.” There and elsewhere, the instrumentalists — including Butt himself on harpsichord — are as playful and lively as they are commanding.

Overall, the recording is cohesive, immediate, and captivating — simply one of the best recordings of Handel I have heard in recent years.