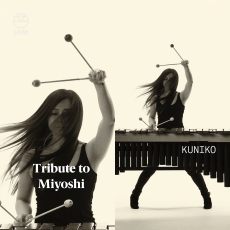

KUNIKO - Tribute To Miyoshi - MusicWeb International

A fine and richly deserved tribute to a distinguished Japanese composer.

Although Akira Miyoshi was certainly one of the most significant Japanese composers of Western classical music – perhaps the major ‘rival’ to Toru Takemitsu (1930-1996), he has attracted relatively little attention in the West (far less than Takemitsu, for example).

A brilliant pianist in his childhood, Miyoshi initially studied composition in Tokyo and then, in 1951, French literature at Tokyo University before, assisted by a French government scholarship, he was able to further his composition studies with Henri Challon and Raymond Gallois-Montbrun at the Paris Conservatoire from 1952 to 1957. Much attracted by French culture, when he returned to Japan he completed his degree in French Literature at Tokyo University (graduating in 1960). He went on to study and then teach at Toho Gakuan School of Music in Tokyo. In the booklet of this CD Kuniko writes “I was fortunate that Miyoshi was the Principal of Toho Gakuan School of Music during my student years. At the time he was at the height of his creative career. Wise and thoughtful, he could be strict and uncompromising about music but he was always calm and gentle to everyone, and I remember him sitting quietly in his office with a sincere expression. Through this album, I hope to pass down Miyoshi’s legacy to the next generation, and also to bring his music to a worldwide audience.”

The list of Miyoshi’s works includes concertos for piano, violin and cello and other orchestral works, as well as several works for Wind Orchestra; his chamber music includes three string quartets, a work (Hommage en Cristal, 1979) for flute, violin and piano and Ombre Scintillante (1989) for flute and harp. As well as an early piano sonata (1958) he wrote a number of sets of smaller piano pieces (such as A Diary of the Sea, 1981); a number of works for guitar, including Epitase (1975) and 5 Poèmes (1985), many choral works and works for percussion (both solo and ensemble). From the 1970s onwards he often used Japanese instruments alongside Western instruments (as in 1975’s Torse IV, a work which puts four traditional Japanese instruments – including a shakahuchi and two kotos, plus a 17-string koto – together with a string quartet). He also experimented with electronics, as in Transit (1969). However, he never abandoned the use of western instruments. (The works I have named above are not intended as a list of Myoshi’s ‘best’ works, they are merely ones I have managed to hear, one way or another).

Most of Kuniko’s previous recordings for Linn have each been devoted to works by a single composer: Kuniko plays Reich (review), Cantus – made up of works by Arvo Pärt (review) - Xenakis IX (2015) and J.S. Bach, Solo Works for Marimba (2017). It is obviously a format she prefers to the mixed recital of works by various composers and in settling on Miyoshi for her latest project of this sort she has had no need to resort to arrangements. The five works recorded here were all composed for marimba.

The earliest work on the disc (it was Miyoshi’s first composition for the marimba, though his first use of it was in his Piano Concerto of 1962), Conversation is a suite in five sections, the titles running as follows – ‘Tender talk’ – ‘So nice it was…Repeatedly’ – ‘Lingering chagrin’ – ‘Again the hazy answer!’ – ‘A lame excuse’ – although there are pauses between the sections, the whole of Conversation is presented as a single track here. There are recognisable speech rhythms everywhere (as a non-speaker of Japanese, I don’t mean specifically the rhythms of the composer’s native language, rather the universal sense of human speech, those patterns of pitch and stress which enable us to recognise that those using a language we do not understand are actually speaking, conveying meaning! The booklet reproduces (in English) the programme note Miyoshi wrote for its 1962 premiere. The composer says that the work “depicts everyday conversations of a family with children”. Of my favourite section ‘Again the hazy answer!’ he says that it depicts a “little boy who comes running in. He’s frustrated and tries to explain but can only say ‘and then…and then…’.” Of the vigorous final section he writes “A lively conversation, but since everyone is talking at the same time, they are at cross purposes. But it doesn’t matter. They just enjoy talking.”

Where Conversation ‘

Ripple is, again, in four sections (untitled this time). But unlike Torse III it has, as its title implies, a non-musical ‘subject’. Myoshi’s own programme note (written for the 2nd World Marimba Competition (which had commissioned the work), held at Okaya in August 1999) gives an implicitly poetic clue to the work: “Even the gentle ripples on the earth’s surface are related to the magma activity deep in the earth. In fact, I am in awe of this gentle sign of the magma’s energy.” The gentle and the powerful are both very characteristic of Myoshi’s music, often heard in close proximity to one another, and Ripple is much concerned with such matters. The use of double mallets in the first section produces music which has clear sense of forward movement along with much harmonic interest, the polyphony of the second section is more obviously linear and the rapid rhythms of the third section evoke ripples in water much as the surface ripples produced by the magma deep inside the earth. This is an attractive and interesting piece which would, I suspect, satisfy for purely musical reasons had it no indicative title, but which takes on an added dimension with the reference to ripples, evoking patterns of movement across the earth in various forms and materials – water, air, sand or whatever.

Kuniko describes the Concerto for Marimba and String Ensemble as developing “from a single consistent theme into a whirl of sound”. A strong sense of drama permeates this work; some orchestral passages remind one of Bartok, others of Dutilleux, whose music Miyoshi has admired since his years in Paris; I mention these names not to suggest that Miyoshi’s work is unduly derivative, but to try to locate the sound-world of this work for those who haven’t heard it. It is the marimbist who produces most of the distinctively Japanese sounds. There are many rapid changes of mood in the work; at times gentle or joyous, at others ominous or solemn. With its power, its intricacy and its emotional range this concerto deserves to be played and heard more widely.

The Six Prelude Études (their titles being ‘Scale’, ‘Harmony’, Contrapuntal form’, ‘Chromatic scale’, Double chords’ and ‘Beat of the same sound (octave)’) which close the disc are ‘studies’ in the purest sense of the term, practice pieces written to help develop the skills of those learning to play the marimba. Kuniko points out that in writing these études Miyoshi has taken into consideration the fact that most of the repertoire for the instrument is modern. So “he uses augmented chords, leaps of augmented sixths or diminished sevenths leading to resolutions. Also, there are consecutive fourths, fifths, octaves, chromatic and altered or diminished scales – tonal patterns that are found not only in classical music but in all genres. In other words, these are essential studies to become a better player.” But for all of their didactic purposes, Miyoshi is too inventive and imaginative a composer to allow himself to be wholly confined by such purposes. He was obviously concerned, simultaneously, that these études should have some artistic value. The results, certainly when played by a consummate marimbist such as Kuniko, make for engaging listening – even if, naturally enough, they are not as rich, in that respect, as the other works on the disc.

The body of helpful documentation in the CD booklet and a consistently good recorded sound (even though the recording information provided implies that that part of the Concerto was recorded in Japan and part in Scotland) adds to the attractiveness of this enjoyable disc.

Three of these compositions (Conversation, Torse III and the Concerto) were premiered by Keiko Abe (b.1937) a Japanese pioneer of the marimba – from 1970 she was another who taught at Toho Gakuan School of Music. Now in her eighties she is still reaching the marimba. In a very real sense, this new disc by Kuniko is almost as much a tribute to her as it is to Akira Miyoshi. Kuniko is ‘passing down’ two related legacies and doing so very effectively in this addition to the series of high-class albums she has made with Linn.