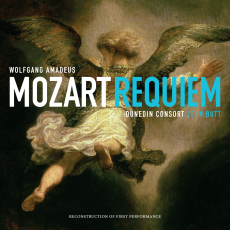

Dunedin Consort - Mozart: Requiem - International Record Review

Mozart's most celebrated sacred work owes its mystique in part to the stories surrounding its composition and the controversy about the extent of his pupil Franz Xaver Süssmayr's contribution to the unfinished score after Mozart's death. Süssmayr enjoyed a deep bond of trust with Mozart, who, on his deathbed, reputedly discussed the Requiem's completion with him. Subsequently Süssmayr claimed to have ‘prepared' the ‘Sanctus', ‘Benedictus' and ‘Agnus Dei', which (apart from the winds and timpani of the ‘Sanctus') are not in Mozart's autograph. According to Mozart's widow, Constanze (in 1826), Süssmayr removed several sheets of paper from Mozart's desk after his death. The quality of much of the writing in the movements Süssmayr wrote suggests they contain some authentic material by Mozart, particularly in light of the mediocrity of his own church music. Yet, Constanze maintained Süssmayr's contribution was minimal and routine (as parts certainly were). Although that claim is largely not accepted today, the validity of Süssmayr's completion of the Requiem, long the standard version, has been challenged.

Scholarly efforts have been made to disentangle the posthumous material from Mozart's and create alternative completions more closely approaching Mozart's intentions. Franz Beyer published a version in 1971, which, among other things, ‘corrected' Süssmayr's instrumentation. Of the later completions, the most radical was Richard Maunder's (1983), which aimed to delete all of Süssmayr's spurious additions (i.e. those Maunder judged to be inferior) and thus discarded the whole ‘Sanctus', ‘Benedictus' and Süssmayr's continuation of the ‘Lacrimosa', as well as also drastically revising the ‘Agnus Dei'. We have now come full circle with a new edition of the Requiem by David Black that seeks (with some corrections) to restore Süssmayr's completion to its original state before later amendments became part of the standard score, such as those made anonymously in the first published edition of the work issued by Breitkopf & Härtel in 1800. John Butt has provided detailed notes about his performance choices.

With Black's expert advice, he has used this new edition as the starting point for an attempted reconstruction of the performances of both the authentic torso of the work (the ‘Introit' and ‘Kyrie' only) performed at Mozart's funeral in St Michael's Church in Vienna on December 10th, 1791, which lasts only seven minutes, and the first public concert of the completed Requiem in 1793. Butt's choir in the funeral version has only eight singers (the four soloists doubled by one voice apiece), accompanied by a small ensemble of single strings and winds except for paired first and second violins. Thanks to Butt's dramatic direction and the choir's fullthroated singing, the work retains its stirring quality, though on a fairly intimate scale. For the main version of the Requiem as completed by Süssmayr, Butt has increased his choir to 16 voices, accompanied by a considerably larger orchestra comprising multiple strings, doubled winds and even a fortepiano. With the assistance of Black, Butt has based these forces on records of Mozart's public performances of his Handel oratorio arrangements in the 1780s, an idea first advanced by Maunder in 1988. Once again, in line with Butt's advocacy of a more soloistic delivery by his choir, his four soloists are also the leaders of each choral register.

Butt directs an at once powerful and attractively nuanced performance of the Requiem. His orchestra is on top form, with especially confident and mournful corni di bassetto and bassoons, as well as vigorous and refined strings. The fortepiano can often be heard amidst the orchestral and choral textures. The three trombonists also deserve mention for the musicality of their important contribution. The choir, despite its slightly rough tone, is agile and fluent. Butt leads them excitingly through the dramatic ‘Kyrie', ‘Dies irae' and ‘Rex tremendae maiestatis', but without unduly forcing the pace. These qualities are also evident in the performance of the complementary piece, a little-performed offertory motet, Misericordias Domini (K222), which Mozart wrote in Munich in 1775 as an academic essay in counterpoint and later sent it to Padre Martini. As Butt observes with amusement, he managed to spin out its one-line text, ‘I will sing of the mercies of the Lord for ever' to well over seven minutes. Its orchestral ritornellos also intriguingly prefigure Beethoven's Ode to Joy theme. On the strength of a set of parts for this work found in the archives of St Michael's Church in Vienna dated by Black to around 1791, Butt has reduced his forces to the same scale as for the Mozart funeral version of the Requiem, which clarifies the tightly written counterpoint. On a standard CD player, and even more when playing the high-resolution version on an SACD player, each voice and instrument is clearly audible and precisely located within the sound-stage. Serious Mozartians will already own numerous recordings of the Requiem in its various incarnations. Despite its flaws, this new one has still fresh things to say about this intriguing masterpiece.