Handel's Messiah - Dunedin Consort - The Berkshire Review

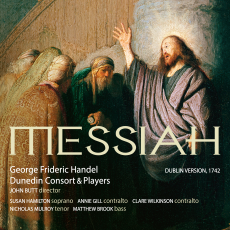

Two of the best recordings of Messiah are among the most recent. They could not be more different; one is a performance of the Dublin version of 1742 by a small consort using historical performance practices and the other is an eclectic text performed by larger forces using modern instruments, Sir Colin Davis' most recent version, a live performance recorded at the Barbican in December 2006; but they are unquestionably among the finest performances of Handel's masterpiece ever, and only a listener who has a seated prejudice against one mode of performance or the other could have any reason to choose between them. One must have both. And don't forget Malcolm Sargent's classic 1945 performance with the Liverpool Philharmonic and the Huddersfield Choral Society, available in a superb transfer on Dutton Records, for something completely different!

John Butt, driector of the Dunedin consort and Gardiner Professor of Music at the University of Glasgow, does not offer the Dublin version as the best or the most original of the ten identifiable versions from Handel's lifetime. Handel customarily composed the music for his winter season at summer's end, and he followed the same method with Messiah, much to the disgust of Jennens, who expected the composer to devote a full year to his compilation. The result was a finished manuscript, which was unusually not adapted to a particular performing group. A conducting score was copied for him, and he made annotations marking the changes for different performances. A crisis in his London career forced him to premiere the work in Dublin, where his forces were smaller and in some cases less skilled than the performers he would have found in London. Later London versions for larger forces survive and are equally valid. Handel made certain cuts and expansions expressly for this performance and rescored particular solo numbers for particular singers, most notably the contralto Mrs. Susannah Cibber, who was in Dublin making a cautious return to public life after an extra-marital affair, which had damaged her reputation at court: hence the unfamiliar setting of "How beautiful are the feet..." as a duet for two contraltos. For historical and musical details I shall refer the reader to the full version of Professor Butt's program notes, published on the Dunedin Consort's site, or to Donald Burrows' indispensable Cambridge Music Guide on Messiah. Above all there is no doubt, as Butt points out, that Handel had a definite dramatic structure in mind for Dublin, one which is vividly projected in the recording.

Following the best estimate of Handel's forces at the Dublin performance, where the intransigent Dean Swift would not release his ordained "Vicars Choral" to participate, the Dunedin Consort's chorus is only twelve strong, and seven of them sing as soloists, providing a seamless flow between solo and full chorus. The Dunedin Players have four first violins, three second, two violas, two cellos, and a single double bass, supported by harpsichord and organ. A tympanist and two trumpets occasionally join in for the grand moments. This minuscule group of virtuosi performing in a church acoustic, intimately recorded by Philip Hobbs with Linn's audiophile techniques and equipment, performed with matchless clarity. Each musical line, even in the richest fugal textures, can be heard, and, beyond that, nuances of expression and color all come through. Even in the full chorus the timbre of the individual singers comes through-all without a sense of dryness or excessively close microphone placement. This enables the singers to focus on the text as their point of departure. Tempo, phrasing, pauses are all planned in order to make the words of Jennens' compilation of Old and (in the third part) New Testament quotations intelligible, expressive, and moving. Handel's musical response to the rhythms of Italian, German, and English was sophisticated and creative, and a good deal has been written about it. Prof. Butt obviously knows this literature, and there can be no better way to study the topic than to listen to this recording. However, this performance is no historical exercise, but a deeply convincing and moving performance which reaches into the core of the work.

The string ensemble likewise shifts between its role as a collection of individual voices, especially in fugal passages, and a massed ensemble with striking character in their playing, projecting a wealth of nuance between long, lyrical phrases and energetic attacks, all perfectly focused on the textual context. John Butt, who conducts from the harpsichord, seems entirely a part of the ensemble. However, his role is all-encompassing, beginning with the research and preparation of a performing score of the 1742 version, and proceeding through the coordination of Messiah's constantly unfolding epiphanies to the management of the overall structure of the work, which comes across admirably, even though the recording was not made live before an audience, although, to be sure, in the context of a series of performances. Since we are always aware of the text, which is always sung with full awareness of its rhetorical impact, the dramatic interplay of the individual numbers is especially vivid, and beyond that the interrelationship of the three main parts, above all, the third, Easter section, which here carries its full weight as the dramatic and spiritual culmination of the work-and very moving it is. However, I should stress that the structural and dramatic integrity of this performance begins with the choice of the 1742 version, interpreted with such penetrating understanding by Professor Butt and his musicians.

The solo group, which, as I observed, folded in with five other singers for the choral sections, was, taken as pure singing in baroque style, with restrained vibrato, of the highest order. Beyond this, there is the advantage of a complete consistency of treatment. As regular members of the consort, they have approached their parts with unity of purpose. Their historically informed singing style is founded on the primacy of the text, which must be intelligible and expressive. This declamatory, or rhetorical aspect of their style is faithful to baroque performance practice, and it only enlivens the expressive qualities of the music, even if we still live with expectations developed in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Ornaments are performed with grace and discretion. In fact both singers and instrumentalists play trills with a loving care and elegance, a nicety one finds all too seldom these days. But overall this espousal of the Biblical text, reminds me of a story about Sargent, when he auditioned a young female singer for Messiah, who after hearing her sing, asked her if she believed in the words she was singing. She answered no, as he expected, and he gently recommended that she seek out other repertoire.

On the other hand, this solidarity does not at all suppress the soloists' individuality. Nicholas Mulroy appears first, showing a handsome, clear tenor with a bright edge, a rich center, and a plenty of weight to support the whole. Matthew Brook is a most impressive bass. He has a sonorous, dark timbre, but all the agility one could want in ornaments and in the more florid sections. Susan Hamilton, one of the founders of the Dunedin Consort together with John Butt, sings with a spare, bright soprano, a truly responsive instrument in terms of balancing melodic line with expressive diction. The mezzo-soprano/altos Annie Gill and Clare Wilkinson sound surprisingly bright in comparison to the plummy contraltos who were a sine qua non in past generations-a welcome development that frees them to address what Handel and the authors and translators of the Bible wrote. In "O thou that tellest good tidings to Zion..." Annie Gill puts her attractively balanced and lithe mezzo range to good use, using a discreet vibrato, while Clare Wilkinson's darker and softer edged contralto, is also enriched with a mild, but somewhat looser vibrato. From the chorus, alto Heather Cairncross joins Annie Gill in the 1742 alto duet version of "How beautiful are the feet," and bass Edward Caswell sings the following air "Why do the nations?" and both are superb.

The qualities I have described are consistent throughout the work. Any random movement can illustrate them well. In "O thou that tellest good tidings to Zion..." one can appreciate both the fine voices and musicality of solo and chorus, as well as the precision and alertness of the strings. As in all the best chamber music, the participants keep a keen ear on each other, and respond to subtle inflections. The rhythmic taughtness of the continuo and the athleticism of the entire group, most impressive when the Prof. Butt pushes the tempo slightly, is wonderful. The chorus "His Yoke is easy, and His burthen is light," which concludes the first part, is a prime example of what this precision, alertness, and flexibility in tempo bring to one of the grand choruses. The energy, attack, and lightness of the running figure in the continuo is splendid.

Scholarship and musicianship have met here as equals to bring about a fresh experience of this central work in the Western canon. It is certainly the most intimate encounter I have had with Messiah, and I found it deeply moving, especially in the concluding Easter section, when the dramatic tensions and moral narrative of the first two parts arrive at their destination in Christian eschatology. But, as a listener, do you have to believe in it to be as moved as I was? Absolutely not. It is part of the human drama.

The recording, which I heard on a physical CD, is on the very highest level. Linn also offer for download direct copies of the studio master which are even superior. Linn also offer free test tracks to help you decide whether these will offer any advantage on your audio system. 180-gram vinyl pressings are also available.