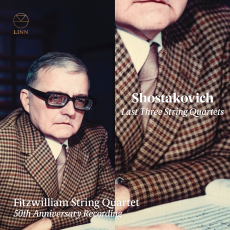

Fitzwilliam String Quartet - Shostakovich: Last Three String Quartets - Fanfare

This release of the last three Shostakovich string quartets is a rarity, a Western recording that can stand beside the great Russian ones from the past. The performances have a unique pedigree, and before describing their musical values, let me recount their source and origin. A remarkable stroke of luck befell a young British string quartet when they crossed paths with Shostakovich in November 1972 in York, England. The program notes give a vivid description of the encounter, which is worth quoting: "An old man sits upright and motionless in a hotel room, peering into a musical score just a few inches from his face. Across the table four raw young musicians are playing for him the music that his long impaired eyesight can barely discern on the pages. But his ears, in contrast, are as sharp as ever: a wrong note there! … a misprint, fortunately, rather than any error in execution. Dmitri Dmitrievich Shostakovich listens intently to his own Fourth String Quartet, then his Sixth, then his Seventh; the players are the Fitzwilliam String Quartet." As recounted by violist Alan George, the last remaining founding member of the Fitzwilliam, being with Shostakovich over two days made a deep and lasting impression, and it gave the four young musicians a mission. As collectors know, Decca signed up the promising but hardly famous quartet to record the first complete cycle of all 15 Shostakovich quartets. In hindsight, what seems more significant is that no other Western quartet achieved a direct emotional bond with the composer. Such a bond had been enjoyed only by two prestigious Soviet ensembles, the Beethoven and Borodin Quartets. The mission paid off, and the Fitzwilliam gained an international reputation overnight. Their Shostakovich cycle, along with a much later one by the Emerson Quartet on DG, was a landmark. But I felt then, as I still do, that the Fitzwilliam didn't have as much to say as the Beethoven and Borodin Quartets, which is understandable. Founded in 1968, the Fitzwilliam was in its infancy compared with those decades-old Soviet quartets, and of course there is the grim experience of living under Stalinism that all Russian artists shared with Shostakovich. To this day the first seminal Russian recordings emanate something that "authenticity" barely describes. Meanwhile, outside the UK the Fitzwilliam Quartet tended to be overlooked. I was impressed hearing them live in London some years ago, and I gave a very positive review (Fanfare 44:1) to a recent Schubert CD, which made clear that through successful rejuvenation of personnel, the Fitzwilliam has escaped the typical fate of veteran ensembles, which leads to depleted energy and a sense of musical fatigue. On short acquaintance Shostakovich impulsively gave the young Fitzwilliam the rights to premiere his last three quartets in the West, so it was fitting, in celebration of their 50th anniversary, that the group rerecorded them in 2018. The results are intense, musically gripping, and moving. Quartet No. 13 was dedicated to the former violist of the Beethoven Quartet and begins with a viola solo outlining a theme based on 12-note tone row. Like Stravinsky, Shostakovich was drawn to Schoenberg's innovation late in his career, but also like Stravinsky, the tone row sounds like Shostakovich, being melodic and melancholy. Here violist George sets the profile of the performance as intense to the point of harrowing. Linn's recorded sound is exceptionally clear and vivid, which sharpens the scraping, plucking, and rapping gestures in the music. Written as a continuous 18-minute arc, Quartet No. 13 is expressively dense, recalling Schoenberg's Expressionist mode in spirit if not vocabulary. What is special in the Fitzwilliam's reading is that beauty breaks through the prevailing sense of mourning. The essence of late Shostakovich, I think, is the economy with which lyricism, loneliness, harmonic density, and the shadow of death somehow cohere into a unified idiom. Quartet No. 14 was also dedicated to a member of the Beethoven Quartet, this time the cellist, and the three movements highlight the cello part, including several duets with the first violin. If Quartet No. 13 feels as austere and haunted as Shostakovich's death-themed 14th Symphony, what comes to mind here is the 15th Symphony—the idiom is more extroverted and conventional, the rhythms giving way to dance, and the themes are occasionally sunny. In the hands of the Fitzwilliam the score's varied gestures and mood swings are captured vividly. You cannot escape the feeling that these musicians are playing the music from the inside (the opposite of the impression made by the Emerson Quartet). All four members are of soloist quality, which shows most impressively in the central Adagio, with its sequence of solos and duets. Quartet No. 15 is Shostakovich's longest and famously consists of six Adagio movements played without pause. Extended lyrical somberness links it in my mind with Haydn's Seven Last Words of Christ but also with the ability of the Beethoven and Borodin Quartets to sustain the longest possible lyrical line. Aware that he had created something extreme, Shostakovich sardonically advised the first performers, to "play it so that flies drop dead in mid-air, and the audience starts leaving from sheer boredom." Today we have music of greater stasis that lasts longer than the Shostakovich 15th's 37 minutes. The piece requires the audience to be in a reflective mood but not a numbed or hypnotized one. The heartfelt performance by the Fitzwilliam brings out the mysterious quality felt in much late Shostakovich, where you are impressed that a master is at work but remain confused about what he is conveying. The center of gravity is funereal, and at times the Fitzwilliam venture into horrified rawness, reaching for the darkness behind the printed notes. In sum, these readings get to the heart of three difficult scores without compromise and with considerable beauty. It's gratifying that the Fitzwilliam Quartet has symbolically closed the circle with such impressive interpretations.